Beltline rail panned by experts for 20 years

Former Atlanta Mayor Shirley Franklin in 2014. Courtesy: LBJ Presidential Library.

Beltline rail followed an unusual path to get this far down the track.

In his 1999 thesis, Georgia Tech grad student Ryan Gravel put forth his vision of a loop of “light rail … to generate redevelopment of the central city.”

He didn’t propose light rail to address an actual transit demand. Rather, Gravel argued, it was needed to spur development along Atlanta’s old “belt line” railroad corridors.

Since then, experts have repeatedly expressed misgivings about Beltline rail. And those misgivings have repeatedly been ignored.

An early example came in 2005. Mayor Shirley Franklin had tasked the Atlanta Development Authority to come up with a long-term redevelopment plan for the Beltline.

The idea of repurposing old rail corridors that encircled the inner city had been kicking around since the early ’90s – first, as a loop of trails and parks in the city’s greenspace plan, then as the exclusively light-rail loop that Gravel proposed.

So the ADA asked an expert panel to evaluate the possibility of transit. The Beltline Transit Panel was chaired by Catherine Ross, a Georgia Tech transportation planning professor who’d earned national acclaim as the founding director of the Georgia Regional Transit Authority. A leading Georgia Tech transit engineering professor, the city of Atlanta’s former planning commissioner and the president of the American Public Transportation Association were among the other members.

What the ADA got back wasn’t encouraging. The paper recommended only considering some segments of the Beltline for transit and thinking about those segments simply as sections of other lines. A complete loop, they concluded, would be a bad idea.

“It seems likely that solely from a transit ridership perspective, portions of this loop will not generate sufficient transit ridership to justify investment in high capacity transit infrastructure,” the group’s Transit Feasibility White Paper concluded. It politely called for “open-minded consideration of the technology options.”

Among other shortcomings, the white paper warned:

Gaps would create “challenges if a circumferential approach is to be adopted.”

The route wouldn’t serve Midtown and other employment centers.

It would be very difficult to create a seamless transfer between a Beltline transit line and existing MARTA stations or even new infill stations.

There was a “surprising … paucity of ridership estimates for different transit options in the BeltLine corridor … given how far the BeltLine concept has come.”

To today’s streetcar critics, this all sounds familiar. Nearly 20 years later, many of the problems identified in the experts’ white paper remain unresolved.

But, to rail boosters, such questions were less important than implementing Gravel’s original vision. His proposal had inspired intown activists, and they became a powerful force in favor of his vision for light rail.

So, later that year, the ADA laid out a compromise. Its landmark Atlanta Beltline Redevelopment Plan named “completion of the entire trail loop and adjacent greenspace acquisition a top priority.” Transit would be developed down the road.

That frustrated light-rail supporters. But it also allowed the rail idea to roll slowly on through the process required to build a new mass transit line in twenty-first century America.

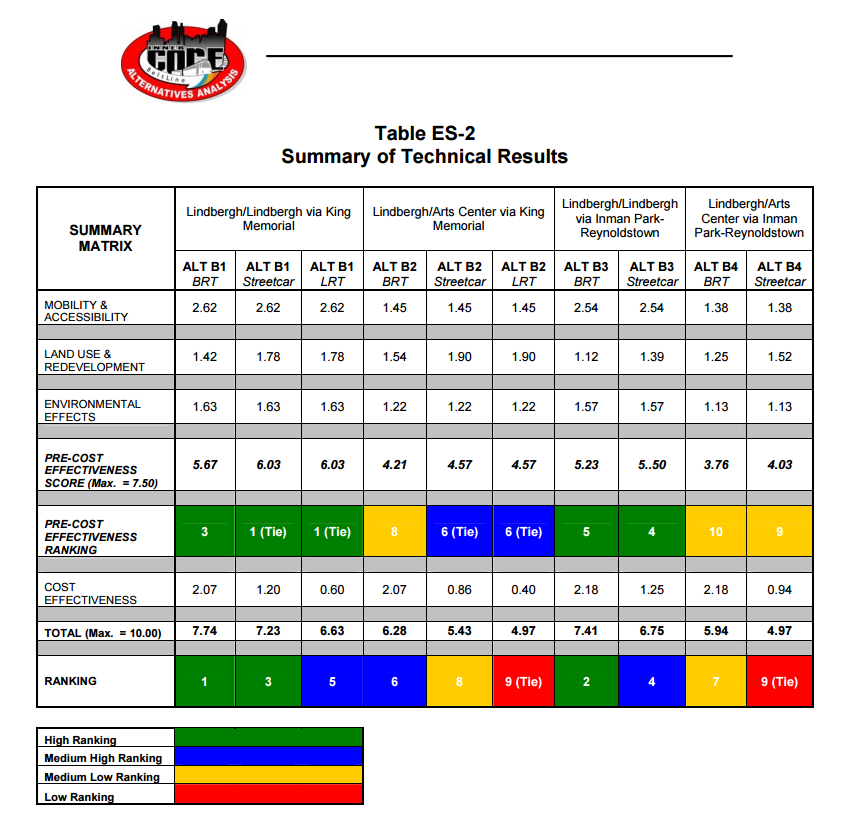

Technical results of the 2008 Inner Core Alternatives Analysis found that the top two options would rely on bus rapid transit.

The pattern would repeat. Each time a closer look identified problems or planners proposed putting resources toward more viable projects, rail enthusiasts pressed to keep the dream alive.

In 2007, as part of a broader study of transit improvements in Atlanta’s inner core, MARTA performed an Alternatives Analysis of Beltline transit. The options considered were narrowly defined, with less concern about the need for the project than with fulfilling a preordained vision meant to drive economic development.

Other than a couple of minor tweaks, the study didn’t consider routes that differed much from Gravel’s original concept. The analysis did evaluate the idea of improving bus service parallel to the Beltline on existing streets, but only “to provide a basis for comparison against [transit on the Beltline].”

The “open-minded consideration of the technology options” that Ross’ panel had called for? It was limited to three fairly similar, fixed-guideway transit modes: light rail, streetcar or bus rapid transit (essentially a rubber-wheeled streetcar).

Inconveniently, the Alternatives Analysis found that “the best performing” option was the only non-rail alternative considered: bus rapid transit. That grade was based on mobility improvements, land use, environmental impacts and cost effectiveness. Light rail, the mode Gravel had proposed, was eliminated entirely due to “fatal flaws.”

But again, Beltline rail enthusiasts let their opinions be known. Fewer than 500 people – about one in every thousand Atlantans – participated in 10 public meetings on the analysis. The predisposition of those participants for rail was unmistakable.

“The public was very concerned about their opinions and preferences being factored into the decision making process,” the report concluded.

As a result, the technical analysis – the analysis part of the “analysis” – was essentially tossed out. The people (or at least the 463 people who participated in meetings) demanded rail, so by God, it had to be rail. The report upended its own findings. In something of a compromise, it concluded that a streetcar, not light rail, would be the best option.

Hard facts and expert conclusions couldn’t compete with passion and conviction. To advocates, the vision was impervious to any implication that it wasn’t a perfect idea, fully formed from the start.

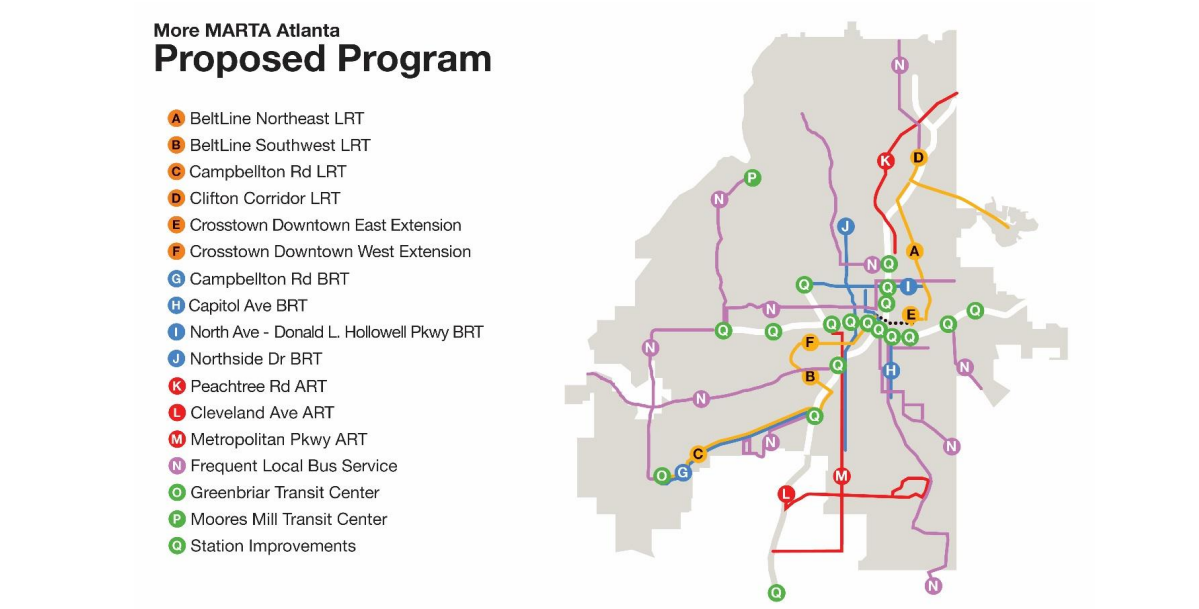

MARTA planners recommended that More MARTA fund “S-Concept” (B, F, E & A) rather than the full Beltline loop.

At times, rail advocates were frustrated that MARTA planners lacked their enthusiasm. In early 2018, for example, amid jockeying for resources from the new More MARTA sales tax, they formed Beltline Rail Now – a pressure group dedicated to a single project above all others.

At the time, it was becoming clear that More MARTA could only fund a small fraction of projects on the capital improvement program’s original list. So, MARTA planners proposed another compromise on Beltline rail: They recommended moving forward only on the segments that were most promising for transit.

In a throwback to Ross and company’s 2005 white paper, the “S-Concept” would extend the existing downtown streetcar both east and west to the Beltline. On the east side, it would run north along the Beltline up to the Lindbergh MARTA station, where it would continue as a Clifton Corridor rail line to Emory University. On the west side, it would run south to the Oakland City MARTA station, where it would connect to a Campbellton Road rail line. (Planning documents referred to all these projects as “light rail,” and although the existing downtown segment is known as the Atlanta Streetcar, the technology and layout along the Beltline have more in common with light rail.)

While the S-Concept still seemed problematic as a solution to the inner city’s transit woes, the staff’s compromise would at least be an improvement. It would avoid unresolved gaps in the Beltline’s northwest quadrant and at Hulsey Yards, and it would focus a bit more on routes that moved workers between homes and jobs.

But it also could drive a stake into the full light-rail loop. Planners had taken public input into account when including the S-Concept in their recommendations. But rail advocates swung into action again. A dozen pro-streetcar speakers spoke at the July MARTA board meeting, another six in August. Among them were Gravel and former City Council president Cathy Woolard, who had championed Gravel’s transit loop from the start.

“We advocate for shifting money in the More MARTA plan toward the Beltline, rethinking the Campbellton Road corridor as a signature BRT project and shifting LRT money to the Beltline in order to build the entire loop,” Gravel told the MARTA Board that July.

At the same time Beltline Rail Now lobbied each of the city’s 25 Neighborhood Planning Units and convinced 11 of them to endorse BRN’s demand for “immediate actions necessary to accelerate light rail along the BeltLine.” (Two more placed conditions on their endorsements.)

To streetcar loop advocates, they were the grassroots taking on faceless bureaucrats who inexplicably opposed what they viewed as the defining idea of the Beltline. Step back for a moment, and it looks like a pressure campaign by organized, well-healed advocates competing for more than their fair share of public funds.

Either way, their aim was to turn the Beltline streetcar into a third rail in Atlanta politics. Nobody wanted to touch it.

Scattered calls for more bus service in other parts of town were no match. The MARTA Board backed down. It added back into the shortened More MARTA list seven miles of Beltline light-rail segments that staffers had nixed.

The light-rail loop that Ross’ white paper had warned in 2005 against and the Alternatives Analysis had found “fatally flawed” in 2007 lived on.

– Ken Edelstein